A Brief Audio Introduction From The Author:

Barely a year into the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, I bought a copy of Faith Ringgold’s first autobiography We Flew Over the Bridge, after watching the HBO Max documentary, Black Art: In the Absence of Light.1 I asked (forced) my father to watch it with me and we both found it to be well-done and very informative. However, it suffered from what I’ve found many documentaries directed by anyone with privilege—the perspectives and presence of everyone else without it. In this case, very few Black female artists were featured and discussed; Faith’s appearance was one of only three Black female artists features (the others were Betye Saar and Carrie Mae Weems). Even her own commentary within the film acknowledges this disparity: “I was not invited to sit down with the men, who were in the struggle with me. I realized I was doing the right thing by becoming a feminist and trying to start a feminist movement in the art world.”

Male-dominated fields have long been harsher environments for anyone who isn’t a man, and it was no less frustrating to see this happen again onscreen. Oh, the intersectionality2 of it all (what it actually is, not what conservatives imagine it to be). In any case, the focus of her segment recounted her efforts to exhibit her own art then later fighting for accessibility of Black artists and later Black female artists in the art world, in New York and beyond. Starting with her attempt and failure to gain an invitation to the Black art collective Spiral. A group of thirteen men and one woman, one of their members, famed collage artist Romare Bearden, declined her inquiry, writing her a nicely patronizing mansplaining letter in return.

In a 2017 interview with CUNY she recounted both this experience and her activism while teaching at the university, making a point that I think is familiar to many of us who have been marginalized: “This is very silly…that I am standing up for people…who are not women. They’re all men, and I’m just here giving my soul and getting no freedom out of it. It’s not smart.” It makes sense then, that her focus expanded beyond Black artists and Black female artists, but to female artists in general. Undaunted, she later sought out Amiri Baraka, then still known as Leroi Jones, and his Black Arts Theater. It was through this opportunity and other art shows that put her on the path to gaining more exposure. Wanting to make a statement in response to the Civil Rights Movement and provide commentary and critique on race relations, she shifted her art style to what she called “Super Realism” and honestly the rest is history.

Something that struck me in reading We Flew Over The Bridge was how much her upbringing reminded me of my grandmother, who is 94 and still fiery as ever.3 Faith’s relationships with her mother and her own daughters I see as parallels to my relationship with my late mother, who was a trained artist. Had she lived, she might have been able to have the second act she very much deserved after I graduated college, embracing social media to showcase her talent. Her artistry was always my inspiration; even after she gave me wrong (but honest advice) that I should focus on a career that would make money, because there’s '“no real future in art.”

Though we never really got to create together my mother always supported my creativity,4 despite her feelings about me pursuing it professionally. She taught me to sew, my paternal grandmother taught me to crochet and any other creative interest I had, I was supported in doing so by most of my family. Even if she didn’t do so formally in her own career, her creative influence showed up in many holidays, birthdays and any celebration with and for loved ones. I have no doubt that her next act would’ve been her “phoenix” moment, had she the chance to explore her passions completely.

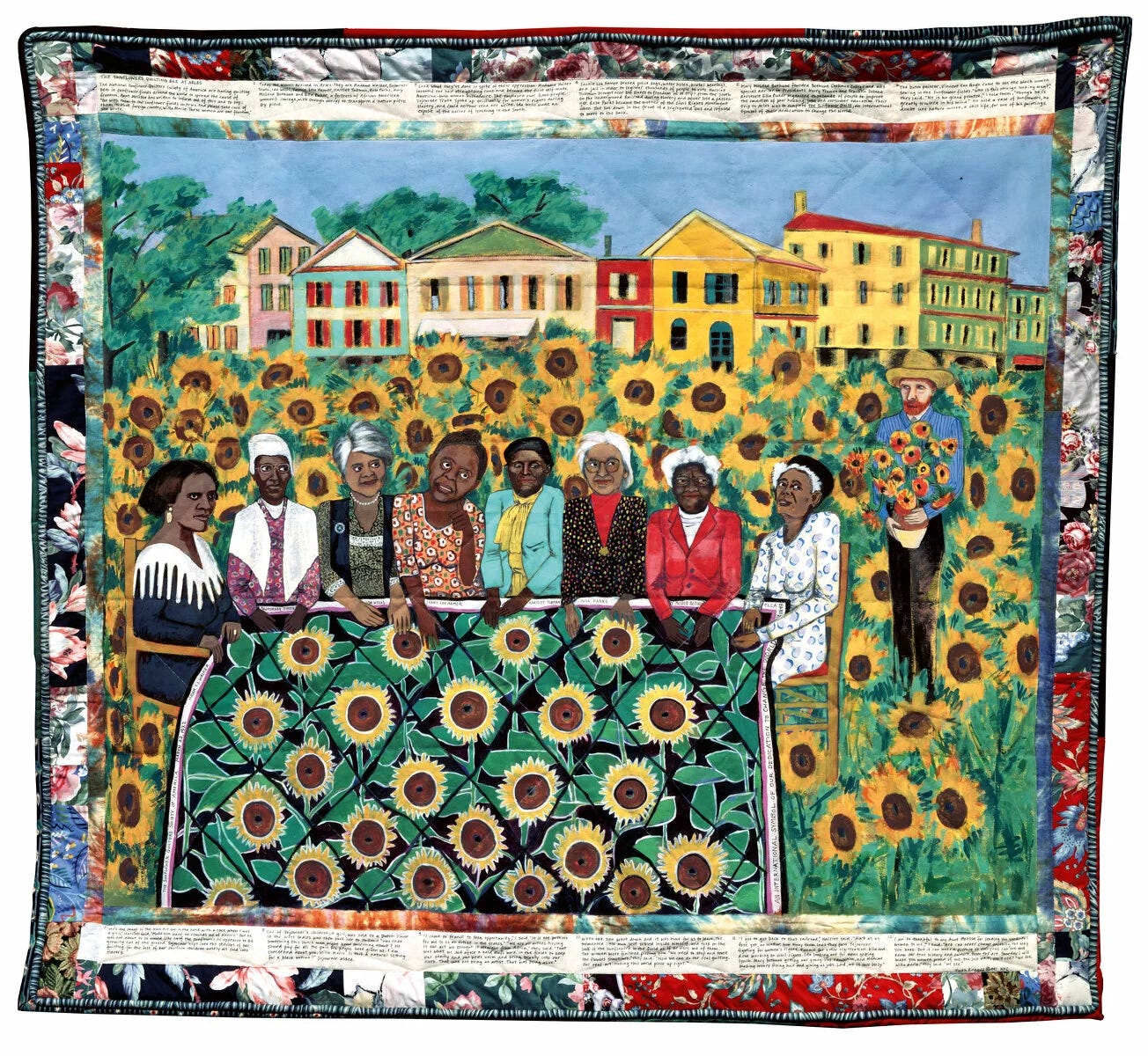

In Faith’s recounting of her relationship with her mother, it was one of both respect and loyalty. A pioneer in fashion design supported and involved the Black community in Harlem though the extent of her impact largely went unrecognized. She supported Faith’s creativity in many ways and was the inspiration for her quilted art. Faith at the time was unaware of the long tradition of Black American quilting and leaned on her mother’s expertise, who started them off . Unfortunately, their first collaboration quilt, Echoes of Harlem, was also their last; she died in 1981, devastating Faith who lamented that her mother never lived to see her many successes. At the time, she was experiencing a career slump and after her mother’s death, her quilt series and performance art gained her recognition and exhibitions nationally and globally, she published children’s books, the first of her autobiographies and more.

I share the feeling that all I’ve accomplished since my own mother’s passing feels slightly deflated, with the one person I wanted to share my successes with the most isn’t around to see it. My belief system however comforts me in that she’s always with me and lives through me; all my ancestors do. Their creative will operates through me. They may not have always been allowed to express that will freely or see the fruits of that effort, but it still lives on through me, and I believe it’s my purpose to carry it on.

All of this isn’t just about Faith’s artwork and my mini memoir. Attacks on freedom of speech, freedom of religion, citizenship, education rights and personal freedoms are happening every day, everywhere, all at once. Many are scared and concerned, completely paralyzed either by fear, fascination or both. Yet any moment is a moment to create art, and our predecessors’ lives have shown that it’s the toughest times that are prime for action. What we create exists in the context of the times we’re living in, that are also echoes of the past. Faith’s American People #20 is both a response to the racial violence occurring across the country in the late 1960’s and a reference to Picasso’s Guernica, an anti-war painting he made after seeing pictures of the aftermath of town bombing during the Spanish Civil War in 1937. From bieng part of The Judson Three5

Whether you’re purposefully trying to say “something” or just letting your emotions guide you, anyone experiencing what you’ve created can see and respond to it. Imagine then, how that response shifts based on a person’s life experiences, cultural background, age and so on. How will kids in the year 2125 respond to what we’ve created today? To what was created in 1975?

We must move on from thinking of our legacies as self-serving individuals only; instead, we should consider how our individual legacies impact the collective itself. What we need more than anything right now, is collective faith — faith in what we want our lives to be like, faith that the future will be better. And then we need to get up and do. Do it scared, do it wrong, but don’t take any of this lying down. Even the freaking Bible says that faith without works is dead. Granted, the effects of capitalism, algorithms and other demands on our mental and physical health have gotten a lot of us out of practice, but it’s still worth trying. We must persist and insist in more ways than one if we’re going to survive and thrive. I’m not going to lie, in a world that increasingly values finding faster ways to do things in order to avoid being inconvenienced and increasing overstimulation to avoid boredom, this is challenging. How we act, what we do and the way we push will take time, yet it doesn’t means it’s not worth doing.

And that effort at any level, can turn into something more dynamic and impactful than originally intended. When no publishers were interested in Faith’s autobiography when she initially shopped her manuscript, telling her that “there was no market for it”, she published it herself anyway, by making the first of her many story quilts. From the performance story quilt recounting her weight-loss journey, to the fictional stories of people living on a city block or a family living during the Harlem Renaissance to famous Black historical figures, her creative storytelling created her own lane while also making connections between the past and present. It took the Metropolitan Museum of Art fifty years to finally accept and show her work and by then, she’d already long been advocating, teaching, and creating. After demonstrating at the Whitney Museum, her recommendations led to the inclusion of Betye Saar and Barbara Chase-Riboud as the first ever black women to exhibit there, in their 1970 biennial exhibition. I could go on and on, but I won’t (because you should really read her autobiographies and story quilts when you get the chance). People can think that literal activism and using your talents and gifts in a way that motivates, inspires and persuades can’t do the same things or be combined, but they can. Some people only get the chance to nudge “the door” open in their lifetimes and others get to kick it down. Either way, there’s movement, and all movements have value.

If my therapist is reading this, then she and my good friend Keisa are more than familiar with my many, many starts and stops on this entire project over the past few years. Beyond feeling anxiety about the outcome, I truly didn’t believe anyone would really care about what I had to say, or that in the great expanse of the internet what I was saying would even stand out. Fortunately, I had the non-unique problem that my main barrier wasn’t hordes of men and/or gatekeeping assholes telling me no — it was just me. Me, myself, and I, and the essence of my parents’ well-intended pressure to succeed, the trust of my family and the guilt of having the chance and freedom to do more than my predecessors. I didn’t know what I wanted this to be or what I’d ultimately do with all this, except that I knew I had to. Inner knowing can come off as very woo-woo to a lot of folks but I had to get to a point where I didn’t care, because it doesn’t matter.

I created “Untitled” (above) in the midst of and after a culmination of a lot of personal highs and lows: graduating with my master’s degree after ten years and 3 institutions, leaving an emotionally abusive relationship, ending one-sided friendships, sustaining and starting healthy friendships, and professional stagnation. I found watercolor-painted paper strips my mother had made and cut and for a long time, I didn’t know what to do with them. One day, I just started gluing them on posterboard; my own haphazard watercolors came later, then gold foil, then collaging. The last time I created any kind of art at that level, my mother was alive and I was uncertain about a lot of things in my future. Now, even though she’s not here physically, I’m a lot more sure, even in the midst of greater uncertainty than before. I just have… faith.

I don’t say this lightly, but you must create. It can be shared but doesn’t have to be. It also doesn’t have to be quote unquote “Art”. I can’t tell you what to do or how to do, only that you must, especially if any of what we’re experiencing makes you feel unsure, anxious, angry. Faith felt compelled to respond to what she was living in. Let your feelings compel you to do the same, in your own way. It should come from your soul and it most definitely shouldn’t be AI.

Because we need you; you and your wonderfully flawed humanness.

You just finished reading some of my art — now go out and create your own.

I still think this film is a great watch for artists, art lovers and educators especially, as it inspired me to write this. Though he wasn’t my focus, artist David C. Driskell (1931- 2020) was an unsung giant in the world of art, art history and higher education. I recommend visiting the Driskell Center at the University of Maryland, College Park to see their current student exhibitions and learn more about his impact.

Crenshaw, Kimberle (1989). "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1989: Iss. 1, Article 8.

These days, her time is well-spent watching reruns of Monk, consistently trolling my father and uncles and writing her memoirs.

Whenever I had to memorize poetry for school, she would tell me that my grandma was a poet and it ran in our blood — she’d usually either wake me up singing Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, or recite Paul Lawrence Dunbar. Guess I didn’t have a choice but to be a writer, huh?

In 1970, Faith and artists Jean Toche and Jon Hendricks organized an exhibition at Judson Memorial Church in New York called “The People’s Flag Show” to protest and challenge ‘flag desecration laws.’ It was also inspired by the conviction of an art gallery owner who exhibited artwork that incorporated the American flag into sculptures criticizing U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

Inspiring read, thank you ❤️

🫶🏾🫶🏾🫶🏾 thank you for letting the words be seen